February 23, 2024

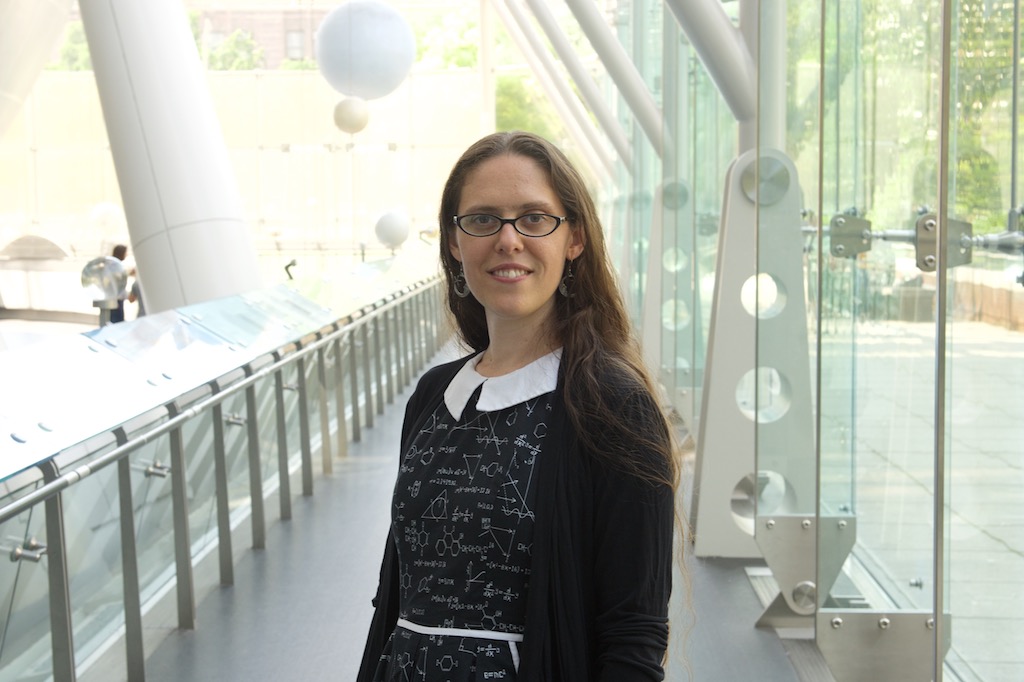

Two astrophysicists, Professors Barry McKernan and K.E. Saavik Ford, have been active members of the international research community focused on black holes and gravitational waves for decades—and just became part of a NASA team with that focus.

As members of NASA’s latest Medium Explorer or Mid-EX mission, the Ultraviolet Explorer (UVEX) space telescope project, Professors Ford and McKernan will be the only community college professors on the 56-member team.

This situates the Department of Science at BMCC alongside centers for astrophysics at prestigious institutions including the California Institute of Technology (Cal Tech), the Goddard Space Flight Center, the UK Astronomy Technology Centre at the Royal Observatory; the MIT-Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research in Cambridge, MA and others.

The UVEX telescope will launch in 2030 as NASA’s next Astrophysics Medium-Class Explorer mission and will survey ultraviolet light across the entire sky, providing insight into how galaxies and stars evolve.

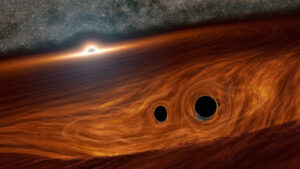

It could also capture explosions that follow bursts of gravitational waves caused by the merging of neutron stars, and may even show the merging of black holes.

The wealth of data the telescope provides will help unlock secrets to the cosmos such as the role of black holes growing in the center of a galaxy, or Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) — one of Professor Ford’s research focus areas.

“In particular, we will focus on gravitational waves, and the role of gravitational waves in the formation and evolution of black holes,” says Ford.

Through McKernan and Ford, BMCC students are part of world-class conversation about astrophysics

The mysteries of black holes and what they suggest about the nature of the universe and laws of physics intrigues students in prestigious doctoral programs around the country.

Professors McKernan and Ford have brought BMCC students into this conversation and included them in research projects contributing to the knowledge base related to black holes, gravitational waves and more.

For example, BMCC students have joined Professors Ford and McKernan in their work as research associates in the Department of Astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City.

Ford and McKernan are also members of the doctoral faculty at the CUNY Graduate Center and members and co-founders of CUNY Astro, a community of CUNY-affiliated astronomers and astrophysicists who collaborate in research, learning, teaching and supporting each other in their love of the cosmos.

In addition to these affiliations, Ford and McKernan lead the combined Laser Interferometric Space Array (LISA) research group across CUNY and the AMNH.

Gravitational waves are the key, but don’t get too close!

Black holes started out billions of times the mass of the sun. Some have condensed down to the smallest bit of matter science is able to perceive. They create regions of space with so much gravity, not even light can escape them.

“Earth’s galaxy, the Milky Way, has between 100 million and a billion black holes, which are mostly dead stars around 10 times the mass of our Sun, spread across the galaxy,” says Professor Ford.

“We also have our favorite black hole, Sagittarius A*, in the center of our galaxy, which is about four million times the mass of the sun and is about 26,000 light years away.”

Scientists didn’t see a direct visual image of a black hole till 2019, though they detected and studied black holes in detail well before that time.

When asked how scientists studied black holes before directly seeing them, Professor Ford has a ready answer: “Gravitational waves!”

In other words, they saw the affect of black holes on other bodies in space.

“We can detect the gravitational pull of black holes on objects outside their event horizon, the place where things can still orbit around a Black hole without being sucked into it,” Ford explains.

“We can see stars that orbit around the supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way, and we can also see gas and dust that are falling into other black holes, small and large, both in our galaxy and others.”

This brings up the question—in science circles as well as popular culture, and movies such as “Interstellar”—What happens if an object gets too close to a black hole?

Professor Ford clarifies that there are different kinds of ‘getting too close’ to a black hole.

Here is one example.

“Because black holes have an ‘event horizon’—the distance from the black hole where the escape speed becomes equal to the speed of light—if you cross the event horizon, it’s the ultimate ‘too close’ moment, and there really is no coming back from that since nothing can go faster than light,” says Professor Ford.

“That also means we can’t *know* what happens on the other side of the event horizon, since no signals can get out to tell us!” she says.

“But assuming the laws of physics don’t magically change when you cross that border, matter will keep falling towards the center of the black hole, called the ‘singularity,’ and will be compressed to infinite density—which would probably be painful. Do not recommend.”

For more information on NASA’s latest Medium Explorer or Mid-EX mission, the Ultraviolet Explorer (UVEX) space telescope project, which BMCC is now connected with, visit here.

For more information on faculty and student STEM research at BMCC, visit the Research and Scholarly Inquiry program at 199 Chambers Street, Room S-636 or call (212) 277-7127.

For more information on astronomy and physics courses in the BMCC Science department, visit here.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

-

Two astrophysicists, BMCC Professors Barry McKernan and K.E. Saavik Ford, whose research focus is black holes and gravitational waves, join international NASA team

-

They are the only community college professors on NASA’s team for the latest Medium Explorer or Mid-EX mission, the Ultraviolet Explorer (UVEX) space telescope project

-

The UVEX telescope launches in 2030 to survey ultraviolet light across the entire sky, providing insight into how galaxies and stars evolve