By Julie Shapiro of the Downtown Express.

The city is not putting up its fair share to rebuild the damaged Fiterman Hall, local politicians say.

The $340 million project is nearly $80 million short, and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who represents Lower Manhattan, says the city owes the remaining money. Part of the reason for the shortfall is that the city spent some money slated for Fiterman on other projects, Silver said.

Fiterman Hall, a classroom building owned by the City University of New York, was rendered unusable on 9/11 when debris from the collapsing 7 W.T.C. deluged the building. CUNY is now decontaminating Fiterman before demolishing it. CUNY then plans to rebuild Fiterman Hall for the Borough of Manhattan Community College — but only if the funds come through.

“This is an eyesore,” Silver told Downtown Express. “The building has to come down and [the new] building has to go up if we’re going to make any progress.”

CUNY already has plenty of money to cover the $16.3 million decontamination and demolition of the building, which should be complete early next year. But as for rebuilding the tower, no one is certain what will happen.

“In order to go forward, [Fiterman] needs the city buy-in,” said Michael Arena, a CUNY spokesperson.

The main reason for the funding shortfall is that the city spent $60 million in Federal Emergency Management Agency funding, which was supposed to go to Fiterman Hall, on other 9/11-related projects.

“They shouldn’t have spent the FEMA money on other projects,” Silver said. “[It] was for this project.”

The city is replacing the money, but the city is counting that replacement toward its overall contribution to the project, rather than providing the replacement separately. That means that the city is ultimately providing less money than it was supposed to under a previous agreement with the state.

“It was supposed to be a city-state joint project,” City Councilmember Alan Gerson said. “The city should fulfill its promise.”

In 2005, the state and city agreed to split any cost overruns on the project. At that point, counting the expected FEMA money, the project needed an extra $40 million, so the state and city each allocated $20 million. Since then, the state allocated an additional $78.6 million, bringing its total contribution to $98.6 million, but the city has not provided a match. By Silver’s calculation, that means that the city owes CUNY $78.6 million.

Now the city is saying that the $60 million that was supposed to come from FEMA is part of the city’s match of state funds.

Silver said last week that he was surprised to hear the city claim the $60 million as a match, and that it does not count.

A city official speaking on the condition of anonymity said they have no intention of providing further match money, since the project’s price tag rose by $100 million in the last year. A CUNY spokesperson confirmed the increase and gave two reasons for it. First, when CUNY estimated the cost last summer, the design work was not complete, so it makes sense that the estimate changed, he said. Second, the original plan was that CUNY would not build out the 14-story building’s top three floors, as a way to save money. But because of enrollment increases, CUNY decided it needed the space sooner rather than later and should include the build-out in the current project, raising the cost, the spokesperson said. Silver said the price change does not get the city off the hook.

After 9/11, FEMA decided to give a lump sum of money to New York City, rather than fielding claims from businesses and institutions individually. CUNY applied for the FEMA funding and was slated to receive $60 million, channeled through the city.

But the city received more requests for funding than they were able to handle and decided to give the $60 million to other 9/11 recovery projects. The city provided funds from its own budget to replace the $60 million in FEMA funds, and that is the money that the city now wants to count as a match of state funds.

FEMA funding is unusual in that the money can only reimburse people for costs they have already incurred. That means the city could not have given the $60 million to CUNY until CUNY spent that amount to build the new Fiterman Hall, the city official said.

In addition to the disputed city funds and the money from the state, CUNY also received $62.7 million in insurance, $15 million from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation and $5 million from the 911 Fund. If the city sticks with its current decision to not give any more money, the project would have a total of about $260 million in the bank, leaving CUNY with a nearly $80 million shortfall.

The project’s $340 million overall cost is broken into $16.3 million for decontamination and demolition, $202 million for construction and about $120 million for “soft costs,” like architects, planners and consultants.

The decontamination and deconstruction will move forward on schedule, Arena said, “But as we get closer to the construction phase, we have to analyze exactly what funding is to pay for that.”

Gerson may hold a City Council hearing on the funding to get more specific answers on how much money CUNY needs and when they need it.

“The bottom line is that the money should be available so reconstruction can continue seamlessly [after demolition],” Gerson said. “The city has the responsibility to shoulder its part of the project to assure this is rebuilt and rebuilt without delay.”

Decontamination on Fiterman Hall was most recently delayed after heightened safety concerns following the Deutsche Bank fire, which killed two firefighters last August during decontamination of that building. Workers started decontaminating Fiterman Hall six weeks ago and expect to finish in another three to five months, said Marc Violette, spokesperson for the State Dormitory Authority, which is managing the project.

After the building is clean, workers will demolish it, which will take another four to six months. That means it will be seven to 11 months until anything could be built on the site, Violette said.

When 7 W.T.C. collapsed into Fiterman Hall on 9/11, CUNY was nearly finished renovating the former office building to convert it into classroom space for the Borough of Manhattan Community College. Fiterman Hall would have opened in fall 2001 with much-needed classrooms, offices, lounges and computer labs.

At B.M.C.C.’s main building on Chambers St., the school is feeling the crunch.

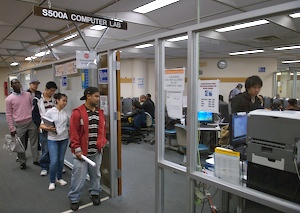

Dozens of computer labs fill every crevice of the building, lining hallways and even the cafeteria. Students stand outside of the labs, waiting for a seat to open up so they can do their work. Many students do not have computers at home and have to type all their papers at B.M.C.C., said Barry Rosen, the school’s spokesperson.

To keep class sizes small, the school has extended class times from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., seven days a week. The administration also converted faculty offices into classrooms, which means that three, four or even five professors crowd into shared offices.

“It’s very difficult,” said Mahmoud Ardebili, a professor of engineering who shares a small office with two other professors. “We are pressured with space — we’re working bone to bone.”

The lack of space and privacy makes it hard to conduct research, and Ardebili has to go elsewhere for private conversations with students, he said.

Before 9/11, B.M.C.C. was cramming approximately 16,000 students into a building meant for 8,000, Rosen said. Since 9/11, the undergraduate enrollment has risen to 20,000, and roughly 28,000 students use the Chambers St. building each week. Rented space near Fiterman Hall is helping ease the crunch, but B.M.C.C.’s main building is still short on space, he said.

“We need this building up as soon as possible,” Rosen said of Fiterman. “We are just bursting at the seams. It’s organized, but you feel as if you’re in the subway at rush hour.”

We thank the editors of the Downtown Express for permitting the BMCC Public Affairs Office to publish the above article.