April 21, 2020

Penelope Jordan, Director of Health Services at Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC/CUNY) — known as “Nurse Penny” on campus — began her role at BMCC 15 years ago with a focus on ensuring that students enter the college having met all their state immunization requirements.

“As a post-secondary institution, we must be compliant with public health laws pertaining to vaccination for measles, mumps and rubella, as well as for meningococcal meningitis,” says Jordan, who also leads blood and bone marrow drives in partnership with Academic and Student Affairs, and represents BMCC on a CUNY-wide, communicable disease committee.

That group, founded in 2009, created a document to guide colleges as they respond to events such as the SARS, MERS, swine flu and H1N1 outbreaks, as well as to chicken pox, measles and TB flare ups on campus.

Weekdays as health services director, weekends as ER nurse

Weekdays as health services director, weekends as ER nurse

In addition to her position as director of health services at BMCC, Jordan has worked as an ER nurse in hospital Level 1 Trauma Centers for 22 years.

She was working in an ER full time, when she began her tenure at BMCC.

“I was seeing the worst suffering on a daily basis,” she said. “It’s difficult knowing that someone will die by the end of your shift — sometimes from natural causes but also from car accidents, suicide, gunshot wounds. There’s only so much of that you can take every day for an extended period of time.”

By shifting her ER role to weekends, “I was able to keep my critical care edge,” Jordan says, and that edge served her well when a wave of COVID cases hit the city’s hospitals.

“We started to see an increase in the ER of people coming in with shortness of breath, chest pains, and symptoms not unlike what we would normally see during flu season,” she says.

“Then March came and all hell broke loose. It was like seeing an explosion. Suddenly everybody who comes in, is short of breath. Everybody has fever, back pain and coughing — a cough you’re never heard before — and they have a sudden and rapid decline.”

One immediate concern for the hospitals was securing a supply chain of personal protective equipment, or PPE.

“Giving patients who are coughing a mask was already standard procedure during flu season,” she says, “but with COVID, the medical team also has to put on a mask.”

While panicked communities stockpiled those supplies, hospitals and medical facilities competed against each other to procure PPE for their staff.

Soon, Jordan says, “The supply chain did kick in, and both the CDC and World Health Organization changed the guidelines for PPE — instead of telling us to use one mask for each patient, we were cleared to use one N95 mask for the whole shift. On top of the N95 mask, we put a simple surgical mask to increase the efficacy.”

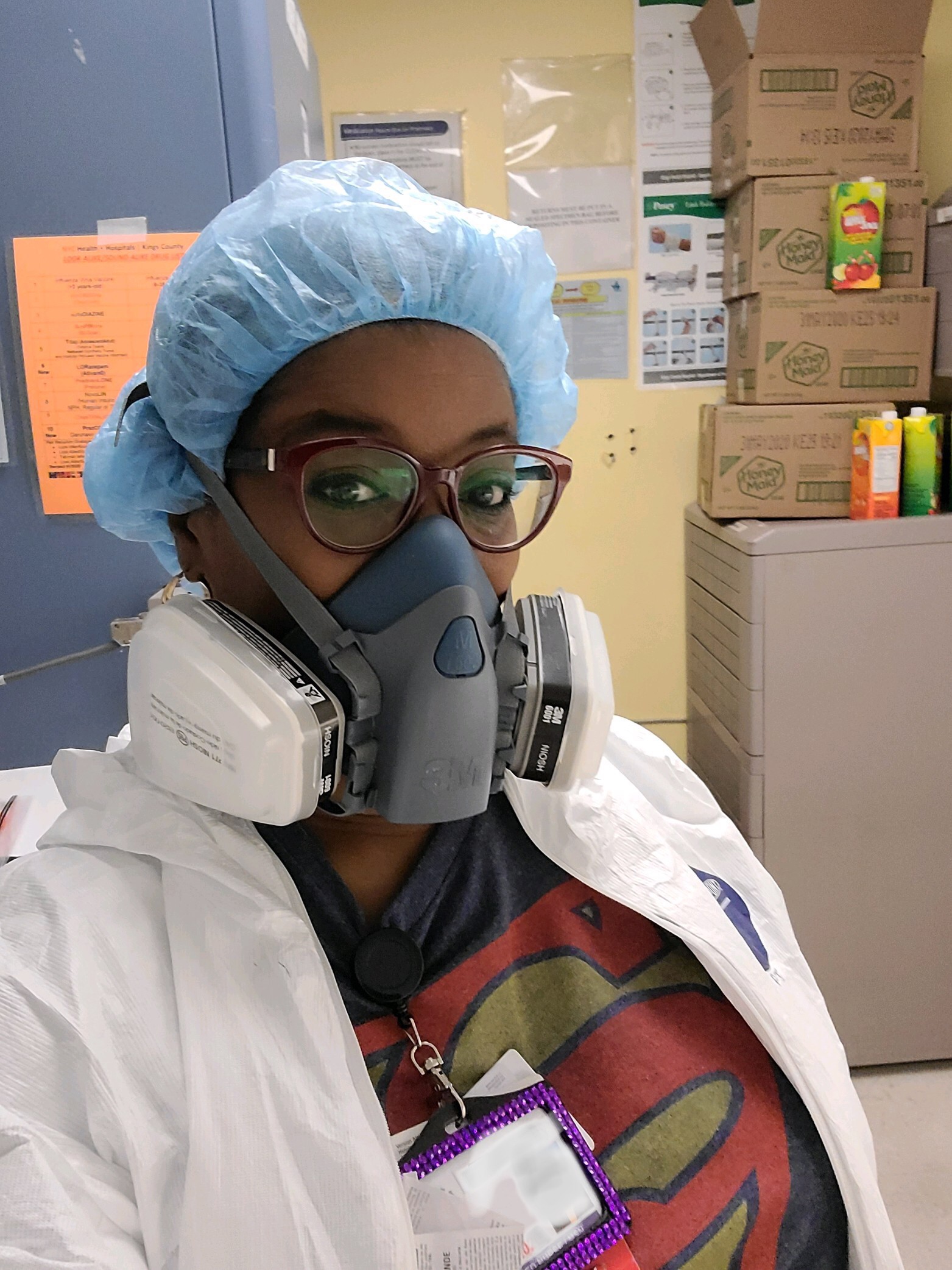

More support came as the Joint Commission on Health Care Accreditation gave the go-ahead to healthcare workers who wanted to use PPE they procured on their own.

“I was able to find a paint respirator with a dual filter and that freed up supplies for others,” Jordan says. “I got it online.”

Hospitals manage the crisis

As the pandemic ramped up in New York City, the hospital where Jordan works repurposed certain areas to increase critical care space.

“In one room we had 20 beds on one side and 40 beds on the other, all of those patients on respirators,” says Jordan. “We were losing sometimes three, four or five people a day.”

As was true for other hospitals in the city, there was also a refrigerated truck parked outside the hospital to help with the morgue overflow at the peak of the crisis.

“I think the worst part is people being separated from their families,” Jordan says. “We try our best to make sure we’re giving information to the families. Some doctors call or use Facetime to connect a patient to their family, and we’re using IPads and other devices to connect families to their loved ones.”

Closure, Jordan explains, is part of the healing process for families facing a loss.

“We’re social beings,” she says. “I really believe your family should be with you when you enter and leave this world — but due to the high infectivity rate with COVID that’s not possible. We’re not trying to be mean, we’re trying to save lives. But this means a lot of families are not getting closure.”

Teams support each other in the ER

“I work with great doctors and a very dedicated team, and they are super supportive,” Jordan says. “One of the things we do is start our shift by doing huddles, like what a football team does, but our purpose is to make sure everyone has their PPE and we’re updated about what’s new on the floor.”

As the crisis unfolded, the medical staff did whatever they could to help each other get through.

“If someone needs to say a prayer, we’ll say a prayer,” Jordan says. “One of our own nurses is in ICU, intubated right now and we all said a prayer for her.”

During one particularly rough shift, when a patient who was expected to live suddenly took a turn for the worse and didn’t make it, the doctors held a debrief session for the medical team.

“One of the residents led us through a mindfulness session, a two-minute meditation where we could express our feelings and do some kind of visualization; like seeing ourselves on a beach, or a boat in the water, to feel more at peace. And then the resident sent an email to everyone with some links so we could use meditation again when we needed it.”

An ER staff develops close bonds, Jordan says.

“You have to remember, ER folks are very sociable. We’ll have potlucks in the ER when we’re working through holidays. We’ll go out for breakfast after a night shift, hang out after work — and we can’t do that now.”

To fill the gap, “We do a lot of social networking, texting each other, checking in to make sure we’re okay,” she says. “One of my colleagues created a meme with another nurse’s expression, and that made us laugh. It helps.”

Someday, she says, the corona pandemic will pass, but life will feel different.

“My takeaway is, appreciate the little things,” she says. “Appreciate that you woke up today relatively healthy. Appreciate the trees are getting greener — it’s spring even though it’s chilly outside. Someday we’ll be able to be together without worrying that hugging somebody is going to kill us. For now, I’m appreciative that I can do what I do on weekends, helping people as much as I can in the ER. And I’m appreciative I came to work today to my office on campus, that I am still able to do that.”

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Health Services Director Penelope Jordan has worked as an ER nurse on weekends since she assumed her role at BMCC 15 years ago

- This keeps her “critical care edge,” she says, as she oversees immunization requirements for new students, leads campus health events and more

- That “edge” came in handy, as Jordan’s weekend ER shifts intensified during the COVID outbreak