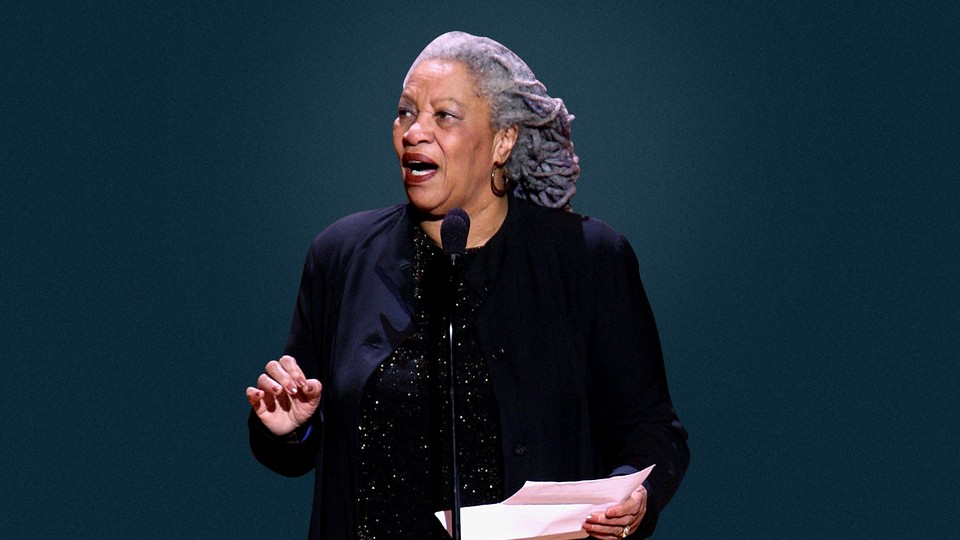

What Toni Morrison Knew About Trump

In her 1993 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, the late author cautioned against the distraction of the “political correctness” debate.

I think a lot about Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize lecture. Morrison, who died last week at the age of 88, was one of the nation’s most revered novelists and thinkers, and has left behind an immense opus that has generated renewed interest. Her acceptance speech serves as a prescient reference to the fact that journalists and political leaders today are wrestling with the language necessary to describe the social and political chaos ignited by the Trump administration. It also doubled as a rebuke to detractors flummoxed that Morrison, who wrote inimitable novels about African American life, was being honored with the highest literary prize in the world. In her talk, she invited the audience to engage in an imaginative thought-game, offering a parable of an old blind woman confronted by petulant children. Her speech, though literary and political in nature, outlines the function of language beyond the boundaries of academia and politics.

The parable begins as such: A group of kids sets out to visit an elderly wise woman, a purported oracle who lives at the edge of town, to prove her powers fraudulent. In Morrison’s retelling, this woman, an American descendant of enslaved black people, attracts these child visitors because “the intelligence of rural prophets is the source of much amusement.” One of the children demands of her: “Old woman, I hold in my hand a bird. Tell me whether it is living or dead.” The old woman, aware of their intent, does not answer, and after a beat she admonishes them for exploiting her blindness—the one difference between them. She tells them that she doesn’t know whether the bird is living or dead, but only that it is in their hands. “Her answer can be taken to mean: If it is dead, you have either found it that way or you have killed it. If it is alive, you can still kill it,” Morrison explained. “Whether it is to stay alive, it is your decision. Whatever the case, it is your responsibility.”

For Morrison, the “bird” was language, and she warned that everyone is culpable for the precarity of language in civil society. “When language dies, out of carelessness, disuse, indifference and absence of esteem, or killed by fiat,” she continued, “not only she herself, but all users and makers are accountable for its demise.” Through this address, Morrison slyly swiped at the national discourse at the time, which focused on how language should be used to define social, cultural, and political realities.

Morrison’s talk came after three years of articles and fierce criticism from the right bemoaning the rise of political correctness. The early 1990s found predominantly white college campuses embroiled in conflicts over language, namely racist terminology. University quads nationwide became a proxy war for conservative ideologues who believed language to be static and rejected its new elasticity, decrying that political correctness was tantamount to oppression. “Ironically, on the 200th anniversary of our Bill of Rights, we find free speech under assault throughout the United States, including on some college campuses. The notion of political correctness has ignited controversy across the land,” said President George H. W. Bush in a 1991 commencement speech at the University of Michigan. “What began as a crusade for civility has soured into a cause of conflict and even censorship.”

The culture and language wars from nearly 30 years ago graft easily onto today’s politics. In 2019, “race,” or rather a complicated and nuanced understanding of racism in all its incarnations, is ascendant in the public discourse. Over the past year, the president’s bigoted rhetoric and signaling escalated with barrages of tweets attacking congressional members of color and asylum seekers, which spurred debate in newsrooms over how to best articulate the meaning of his words. In March, the Associated Press updated its stylebook, instructing newsrooms on how to avoid ambiguous descriptions such as “racially charged” and “racially motivated,” which often stymie the public’s understanding of racism and its tangible effects. Still, many mainstream news organizations continue to rely on the convenience of inventive euphemism, dampening the impact that more direct language could have in framing the administration’s racist cruelty.

Morrison’s words back then seem prophetic:

Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek—it must be rejected, altered and exposed.

Still, Morrison’s speech repudiated the idea that language uttered by those with good or clear intent would inoculate minorities against the rants of despots or demagogues, ignorant, thoughtless people who espouse racist ideas. “There will be more of the language of surveillance disguised as research,” Morrison added, “of politics and history calculated to render the suffering of millions mute; language glamorized to thrill the dissatisfied and bereft into assaulting their neighbors; arrogant pseudo-empirical language crafted to lock creative people into cages of inferiority and hopelessness.” Though the old blind woman in the tale is aware that language may fail to guard against tyranny, “word-work” is still sublime, Morrison said, aiming to define the ineffable, “[arching] toward the place where meaning may lie.”

Morrison understood the challenge then and now: reckoning, via language and imagination, with a complete history of how this nation was formed. The stories people tell themselves of themselves are extremely limited, and the bulk of the conflict rests with the imagination itself—of who can be an American. “The term ‘political correctness’ has become a shorthand for discrediting ideas. I believe that powerful, sharp, incisive, critical, bloody, dramatic, theatrical language is not dependent on injurious language, on curses. Or hierarchy. You’re not stripping language by requiring people to be sensitive to other people’s pain,” Morrison said later, in a 1994 interview. “What I think the political correctness debate is really about is the power to be able to define. The definers want the power to name. And the defined are now taking that power away from them.”

By the end of her Nobel speech, the children in the parable begin to understand how “the choice word, the chosen silence, unmolested language surges toward knowledge, not its destruction.” They abandon their questions to tell a story of their own making, their imagination extending beyond the limits of the language imposed on them to define reality anew. Morrison’s 1993 address is scripture for the modern era.